Software piracy has been around basically since the inception of software, and copy protection methods almost as long, so today’s discussions around DRM really isn’t anything new. All the way back in 1976, a certain Bill Gates wrote an open letter to a computer hobbyist club complaining that “most of you steal your software.” Back in those days, however, even he considered copy protection to just be in the way and wasn’t an advocate for it.

Software piracy has been around basically since the inception of software, and copy protection methods almost as long, so today’s discussions around DRM really isn’t anything new. All the way back in 1976, a certain Bill Gates wrote an open letter to a computer hobbyist club complaining that “most of you steal your software.” Back in those days, however, even he considered copy protection to just be in the way and wasn’t an advocate for it.

There has been a huge number of more or less creative methods to prevent people from making illegal copies of games and other software, but the ones we think are the most interesting (and amusing to look back at) are the ones involving actual physical extras. Though these days most copy protection is mostly software based, there was a period back in the 80’s and early 90’s when software developers pursued other methods, and game creators tended to be extra inventive.

Here are a few gems from that era.

Lenslok

In the early 80’s several games (most famously Elite) on platforms like Commodore 64 and Sinclair ZX Spectrum shipped with something called the Lenslok. It was a small plastic device that contained a row of vertical prisms. A scrambled code would be shown on the screen, and only by viewing it through the Lenslok could you decipher it and start the game.

One big problem with the Lenslok was that it couldn’t be calibrated for all screen sizes, so some people with very large or very small screens couldn’t descramble the code. There were also instances where incorrect Lensloks were bundled with games, which probably wasn’t a very popular move.

Above left: The Lenslok in action. Above right: The Lenslok that came with Elite.

Code wheels

In the late 80’s and early 90’s several games shipped with a special code wheel that was necessary for being able to play the game, often related to in-game mechanics.

For example, The Secret of Monkey Island came with a “Dial-A-Pirate” wheel, and Monkey Island 2: Le Chuck’s Revenge came with a “Mix’n’Mojo Voodoo Ingredient Proportion Dial” wheel.

Above left: The code wheel for The Secret of Monkey Island. Above right: The code wheel for Monkey Island 2: Le Chuck’s Revenge.

Code books and manuals

One of the more common systems back in the day was manuals and code books with content that you needed to complete the game.

Some games for example demanded that you entered word X on line Y of page Z of the manual. More creative variations existed as well, for example King Quest III had sections where the player needed to create magic spells, but could only do so with the help of magic formulas from the game’s manual.

Many of these manuals had key sections printed on dark paper, which made photocopying more difficult.

Dongles

Dongles started appearing in the early 80’s and were used both for games and commercial software of other kinds. The dongle would need to be plugged in to the computer somehow, often through the serial or parallel port. Without the device plugged in, the software wouldn’t run.

The very first program to use a dongle was Wordcraft on the Commodore PET in 1980. Its dongle (the inventor named it so for lack of a better word) connected to the computer’s external cassette port and was two cubic inches large (32 cubic centimeters). We were unfortunately unable to find a picture of it.

These days some software uses USB dongles for copy protection, so we’re not rid of them yet. Dongles are pretty unpopular among users (it’s arguably one of the most hated software protection methods ever), so usually only more specialized and expensive software get away with using them.

Above: A parallel port dongle.

Feelies

These were extra items included with Infocom games. Feelies were themed after the specific games and just as with code books they often included something that was necessary to be able to finish the game, thus acting as an entertaining form of copy protection.

For example, the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy for the Commodore 64 came with things like “Peril Sensitive Sunglasses” (opaque black glasses), the order to destroy Earth, Pocket Fluff, a Don’t Panic! Button, and a Microscopic Space Fleet (an empty plastic bag).

There were also other companies that included extra goodies simply to entice people to buy the game instead of copying it, but without any actual copy protection involved.

Above: Some of the feelies for the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy video game.

When games decided you were cheating…

There were also some fun ways that games reacted if you failed to properly enter your code or whatever it was that was necessary to play the game, or if the game overall decided that it had been copied illegally.

Here are a few examples:

- Starflight would send unbeatable police ships that destroyed your spaceship.

- Superior Soccer would make the soccer ball in the game invisible, thus making it impossible to play it.

This kind of crippling is something that some games still do if they think they are being played from an illegal copy.

Fond(ish) memories of a bygone era

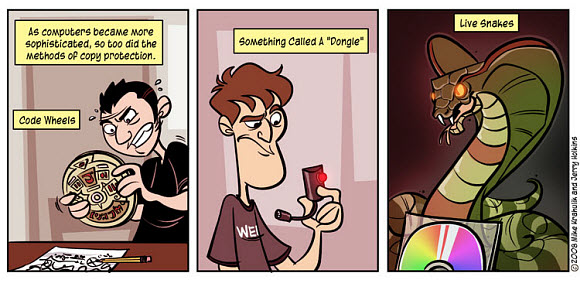

These old copy protections methods have led to fond – and sometimes not so fond – memories for a lot of gamers. We’ll finish off with a comic strip from the excellent guys at Penny Arcade, which we couldn’t help but share with you here:

Now all that is missing is sharks, with lasers on their heads!

Image credits: Feelies from Álvaro Ibáñez (ours is slightly cropped). Dongle from Wikipedia. Code wheel for Monkey Island 2 from Scummbar.com. Small Monkey Island 1 code wheel from Gamesradar and the larger from Hector Pierna Sanchez. Lenslok images from c64-wiki.com and The Bird Sanctuary.