We all know the by now woeful tale of Internet Explorer 6, which close to a decade after its arrival still has a significant share of the web browser market. Its users have been extremely slow to abandon it in spite of there being two newer and much improved versions of Internet Explorer freely available. And this is with Microsoft actively encouraging an upgrade. You could even argue the same for Internet Explorer 7; why haven’t the vast majority of Internet Explorer users switched to version 8 by now?

This conundrum made us wonder how the other web browsers fare when it comes to getting their users to upgrade to newer versions. How quickly do Firefox, Safari, or Google Chrome users upgrade their browsers when new versions arrive?

We have studied the upgrade pattern for Internet Explorer, Firefox, Google Chrome, Safari and Opera and found some drastic and quite interesting differences.

Although we don’t have actual upgrade statistics, we can see how the market share for the various versions of a web browser changes, and that is good enough for our purposes. We used data from StatCounter, who provide browser statistics based on tracking of approximately three million websites globally.

Since we began this article with Internet Explorer, let’s now move on to a very different example: Google Chrome. (We’ll revisit IE a bit further down.)

The upgrade pattern of Google Chrome

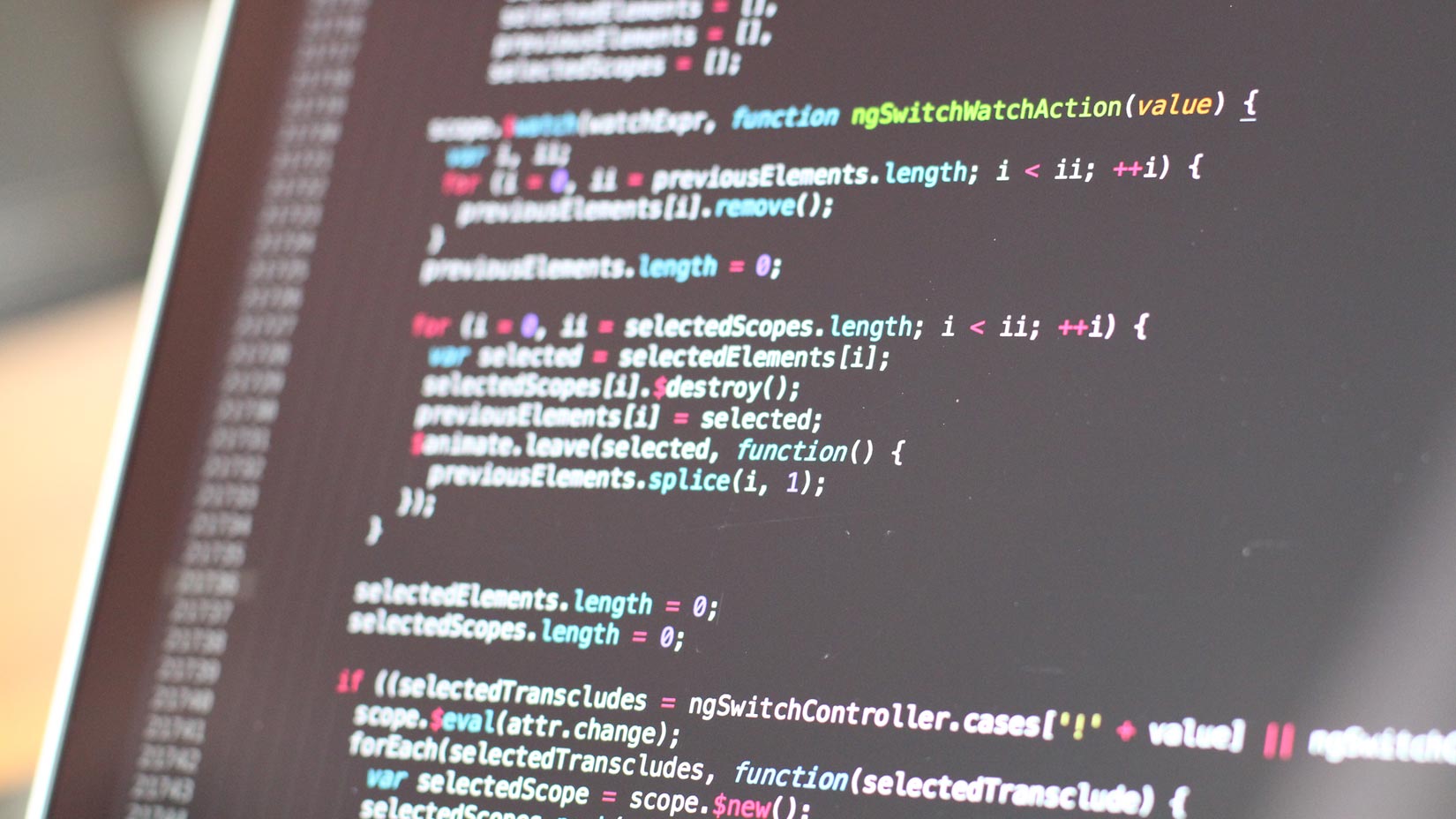

What’s interesting about Google Chrome is that Google has taken a very different approach to upgrades compared to other browser makers. Their mantra: Don’t ask the user to upgrade, just do it.

Google Chrome handles its upgrades in a completely automated fashion, even for a completely new version of the browser. While other browsers will ask the user for approval to move from version 1 to version 2 (just an example), Chrome will just handle that in the background and move ahead with the upgrade.

If you think about it, this mirrors the way web apps work, i.e. updates go through to all users so everyone is using the same version of the software.

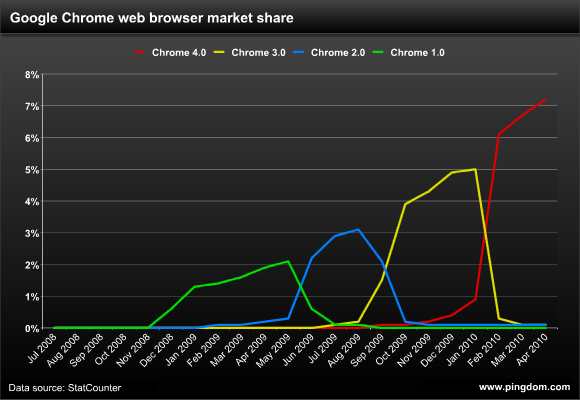

Chrome’s automated upgrade schedule becomes exceedingly obvious when you look at the chart here below, where you can see each new version replacing the one before it almost entirely within a month or two. (Presumably Google staggers the upgrades so they don’t all happen at once and overload their servers.)

The upside of Google’s automated upgrades is user convenience and that all users will actually be running the latest version of the software, which can have positive security implications as well.

The downside is that the user loses control over the upgrade process.

What is also apparent when looking at this chart is the rapid pace of upgrades to Google Chrome. It’s gone from version 1.0 to 4.0 in little over a year. No other browser we know of is even close to this pace.

The upgrade pattern of Internet Explorer

Microsoft, perhaps due to a combination of being the default browser in Windows and somewhat conservative company policies regarding browser usage, has an exceedingly slow rate of change when you compare it to the other browsers in this study.

IE 6 is the last of the old generation of browsers, and it’s not going away anyway near as fast as we’d all expect. The only good thing that can be said about it right now is that it is, as of September 2009, the least common version of Internet Explorer, since that is when version 8 passed it in popularity (ok, market share might be a better word than popularity here).

The upgrade pattern of Firefox

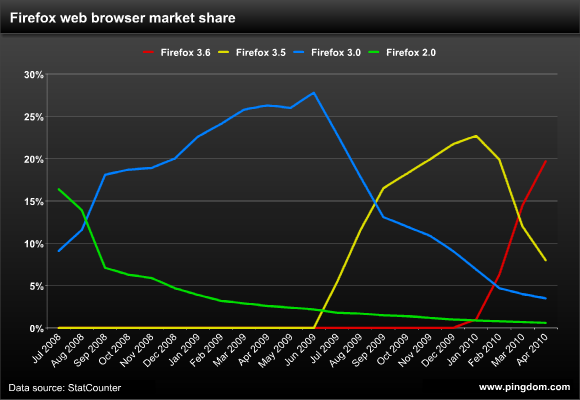

Compared to Chrome and IE, Firefox has managed to find some sort of middle ground in the way it handles upgrades. Upgrades are handled more aggressively than IE, but doesn’t go to the extremes of the fully automated Chrome. Minor upgrades (such as 3.6.1 to 3.6.2) are handled automatically, but the user has to approve any big upgrades (such as from 3.0 to 3.5).

(Note: We didn’t include Firefox 1.5 in the chart since it was pretty much flatlined at the bottom.)

An interesting observation here is that it takes a new version of Firefox less than three months to overtake the previous version.

One way Mozilla goes about this is to give users who after a couple of months haven’t upgraded a gentle push in the right direction. Quoting from Mozilla’s developer blog:

In the past 50 days, Firefox 3.6 has been downloaded over 100,000,000 times […]

Starting today, users running older versions of Firefox will be offered the choice of upgrading to Firefox 3.6. We’re presenting this upgrade offer for our users who may not realize that a new version is available.

The upgrade offer Mozilla started using looks like this:

That same blog post on the Mozilla developer blog goes on to note:

The offer screen will only appear after 60 seconds of keyboard inactivity to ensure we don’t get in the way of anyone’s activities. If a user declines the offer and later regrets that choice, they’ll be able to get it again simply by selecting “Check for Updates” from the “Help” menu.

The upgrade pattern of Safari and Opera

For the sake of completeness we have also included Safari and Opera, although we won’t go into similar detail here. We’ll let the charts speak for themselves.

Please note that the below chart for Opera doesn’t include the newly released Opera 10.5.

The dip for Opera 10.0 that you see at the end is most likely caused by its users migrating to Opera 10.5, although that version wasn’t included in the stats we downloaded from StatCounter. The release of Opera 10.5 matches the drop perfectly, since the beta was introduced in February and the final version in March.

That also means that Opera is doing a very good job in getting their users to upgrade rapidly.

Conclusion

The different patterns we’ve seen above indicate two things:

- Different approaches to making users upgrade. Completely automated, or aggressive promotion of new versions, or a more laid-back approach? These charts all tell a different story.

- These browsers have different types of users. Upgrade behavior will in most cases be tied to the kind of users the browser has attracted, with IE’s slow upgrade rate partly being the effect of a user base that is what you might call technologically conservative. To name an example, only around 14% of Pingdom’s users access our control panel with IE, but Chrome accounts for 21% and Firefox for 51%. This is very different from the internet average, where IE has more than 50% market share and Firefox and Chrome significantly less, but it’s a reflection of the fact that our users consist largely of webmasters, sysadmins, web designers, and site owners. In this case, Firefox and Chrome has attracted a more tech savvy audience (on average), which may be more inclined to upgrade to the latest version quickly after it arrives. The share of technical users each browser has will affect the upgrade pattern.

Web browsers are among the most widely used applications in the world and even those of more modest popularity like Opera have a huge user base. When it’s time to upgrade to a new version, they have to convince millions of people to do so.

Google is an extreme example of pushing upgrades out to everyone. Although there will be people who criticize their approach with automated upgrades, Google’s strategy has a lot of merit, and most users are bound to find it quite convenient.

Getting users to upgrade to the latest version isn’t just good for the users, it also has plenty of positive side effects for the browser developer. An obvious benefit is that with just one version out there, or close to it, the support burden should diminish significantly.

The future will tell if more developers switch to the approach Google is using with Chrome. It is obviously working very well for them.

Suggested further reading: Does Internet Explorer have more than a billion users?